Valuable Lessons from the Forest of Machu Picchu

VALUABLE LESSONS FROM THE FOREST OF

MACHU PICCHU

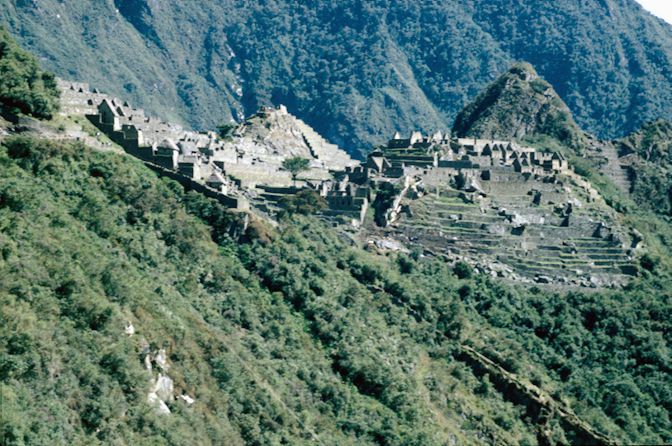

The first thing that comes to mind when discussing Machu Picchu is its Historic Sanctuary, or the Yakhta. Because of this part of the site, which holds a lot of cultural significance, hardly anyone takes into consideration visiting the forest of Machu Picchu, which carefully hides the site’s most important secrets and teachings to our present.

The most significantly relevant place in Machu Picchu, in fact, is not the Yakhta. It has always been the forest, the one that nobody wants to visit. The world knows all about the stories of how Hirgahm Bingham discovered Machu Picchu, but what did he do when he went to the forest? He burned it. The Inca knew better. They also cut the forest to open up space, but they had a way of restoring its habitat, which shows they had expert knowledge of the complexity of the woods themselves. The Incas would have never thought that a single human being could more intelligent than the forest. In fact, the reason why the landscaping of the site is so elaborated and sophisticated is because they always believed that the network created by those plants was more intelligent than their own planimetric planning. The Inca, the Chacha, and all communities who worked or lived in the forest never looked at it as wilderness, but as a complex network from which they could learn about life.

The forest of Machu Picchu, just like any other, is home to millions of living species, from huge trees to small plants, wild animals and small insects. The whole build up of the forest creates one huge network that runs so deep that a mere human could not begin to comprehend. For example, let’s consider the Chiwawako tree in the Machu Picchu forest. A single one of these has roots that grow and expand through a radium of roughly 40km under the earth. The roots of the Chiwawako decide what the balance of the nutrients of all the other plants’ roots is. Considering that these trees live for thousands of years, a single Chiwawako has the ability to plan, through its roots, the balance of all other near inhabitants.

Therefore, when one decides to cut one of these trees, they are potentially cutting 40km of nutritional balance for the forest. Can you just believe it?

The sad truth however, is that today, with the advanced technologies that we have developed, the destruction of these trees, along with millions of other living species, is continuously happening, disrupting the balance of life in the site, and on Earth. Instead of evolving forward, we as humans are moving backwards. This is why Machu Picchu is so important as a Heritage Site. It conveys the message that there is a different approach to this, a way of treating the forest with intelligent and positive outcomes.

“I don’t believe in people doing marches on the street, saying ‘Save the Chiwawako’, because nobody knows it. This is why it is important to create awareness.” (Adine)

Machu Picchu still teaches us today, in the 21st century, to pay respect to the intelligence of life and its ability to create a network of that combine species in a way that is healthy for everyone. We are currently living in a time when humans have pretty much depleted our planet’s resources, as we always considered them as an endless stream of something that has no intelligence or goal of its own. However, the truth is, it was never there for us. Nature has its own order and, by not paying attention to the cycle of life of these natural resources, we run a very big risk today.