Machu Picchu’s Undiscovered Tea Plantation

BEHIND THE WALL

MACHU PICCHU’S UNDISCOVERED TEA PLANTATION

You may be asking yourself, why is the Chief of the Machu Picchu Archaeological Park posing in front of a broken wall in the middle of a field? Well, what may seem like a funny shot is actually a picture a very intricate and meaningful story.

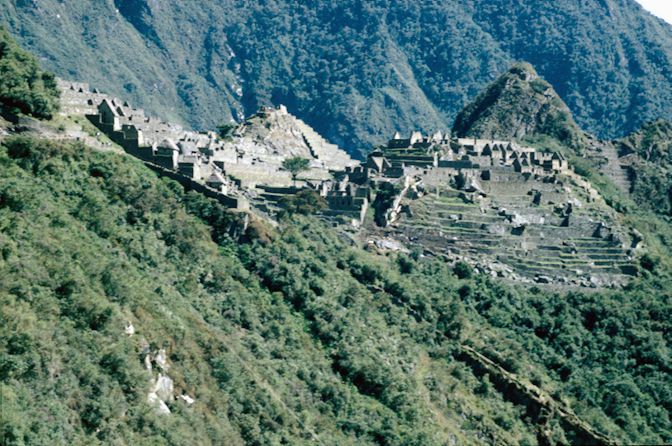

In July 1987, Fernando begins excavation work in a defined area of the site called muralla de Mandor. As you may be able to tell from the picture above, on one side of the wall trees are cut and the ground is not as fertile, while on the other side vegetation is thriving. This is exactly what Fernando noticed when he first got to the area, urging him to investigate the plants on each side further. Surprisingly, he found that the greener leaves on the right side of the wall belonged to huge tea plants, which measured from two to three meters in height. These plants were in fact planted in 1937 by the Maldonado family, who decided they would really like to have their own tea plantation. This may sound absurd, but at the time, there was no law prohibiting the act of planting vegetal species which were endemic to the area.

Around the same time, a German scientist found himself in the area for explorative purposes. His attention was suddenly caught by this specific wall and he decided to take some pictures, which were later inserted in a book reporting on the site. However, his writings were later burnt by the Nazis because of his Jewish heritage. Adine Gavazzi explained:

“As you may imagine, it became very difficult to find a copy of those pictures and that text, even though many people knew they existed. There are actually many individuals who are still determined to find his book and his original pictures. It’s almost like a treasure hunt!”

However, someone had provided an even earlier visual representation of the site. Augusto Berns, a German engineer, visited Machu Picchu in 1861 and made drawings and sketches of the same wall, together with a very big stairway in the same area. For the same reason, scientists and adventurers got interested in his productions as well, which were the only resources available to the public. Now this is exactly what Fernando saw. Berns’ drawings. He knew they looked the same as the long lost German books, and decided to excavate right where the sketches were made, in hopes to find the original wall and stairway.

Not only does Fernando find the wall, but he also finds these very interesting tea plants. Soon enough, he also realizes that there are many other areas around the excavation that were cultivated in ways that were not supposed to be used for the endemic soil. This left him pretty shocked, as by the time the eighties came around, laws had been put into place for the protection of the Machu Picchu forest.

“Even though it was an unusual discovery, the team definitely made the most of it. Fernando actually used some of the tea for the excavation workers’ breakfast. They were around two-hundred, and needed something to drink after all that time working under the sun.”

However, Fernando was caught by surprise even more when he came back to the same area following the rain season, during which excavations were not allowed. When returned, the area of la gran caverna and its terraces (picture below on the right) had entirely been cultivated with plants like corn and coffee. This is an intrinsically Andean way of cultivating food, which made Fernando suspect that the were families who lived on the park’s grounds and who were still growing their own food, even if not native to the park’s natural landscape.

“There was this one family who, during excavation time, was very happy to notice that some unknown people were ‘regularly cleaning their terraces’. Not for one second did they think it was wrong to cultivate on archaeological Inca terraces! It was their way of doing agriculture and would not easily see the difference between what was theirs and what was the Incas’.”

Now, this became quite a difficult task for Fernando, as he could not convince local inhabitants that they could not implement this specific way of growing crops. The paradox was: Machu Picchu is a national monument and should not be violated, while at the same time local people have every right to cultivate their own land.

How are endemic species of the forest protected in Machu Picchu, then? Generally, locals have the right to run their own farms, however, they have to do so in a way that corresponds to the traditional Inca technique of doing agriculture. These people were doing exactly that, but, unfortunately, majority of the plants still had to be eradicated. This is because they interfered with the excavation, which was going to benefit the archaeological park as whole, deemed as more important heritage to the community.

“This is what happens when material heritage meets with immaterial heritage. As an anthropologist, Fernando would not have removed those plants, but as an archaeologist, he had to intervene, for the sake of the excavation itself.”

The fight to eradicate non-endemic species in the Machu Picchu forest and the Cusco region still goes on, with the hope of seeing a more sustainable and healthy natural surrounding in the future.